Ebikes E-volution Article

This is an article that was originally written by Justin for Momentum Magazine in spring of 2010. The pitch was to offer an insight in the DIY and Hacker side of the ebike movement that we felt had largely been overlooked at this time when the press was just finally starting to realize that electric bicycles exist and were a 'thing'. As it is no longer on their site we decided to post it here to still be accessible.

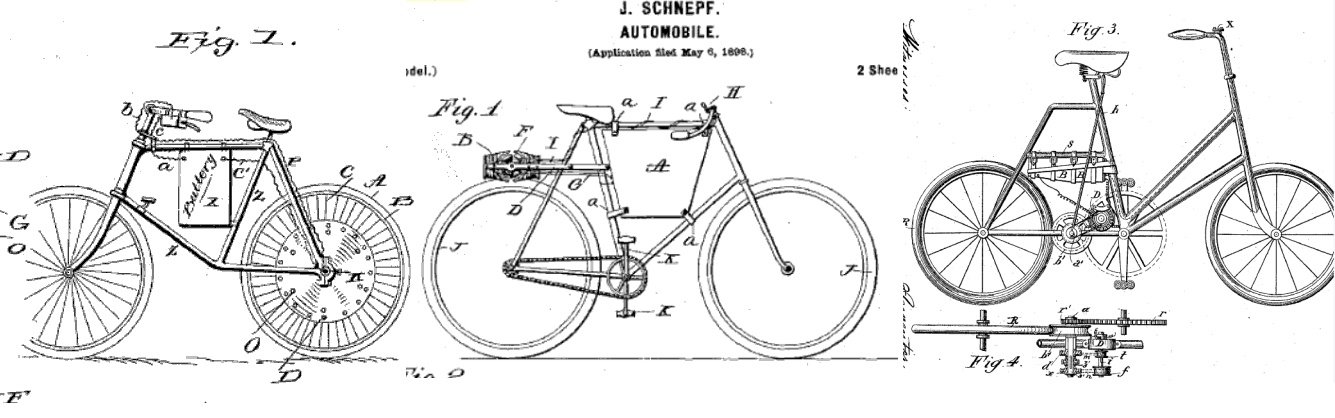

In 1895, Ogden Bolton Jr. was issued US patent number 552,271 for a new and useful improvement in "electrical bicycles" in which the entire motor assembly was tidily built into the rear wheel. With a battery pack secured in the triangle frame and throttle wires going up to the handlebar, the patent diagrams bear uncanny resemblance to the modern hub motor electric bike. Another patent from 1899 shows a friction roller drive on a pedal bicycle that looks just like the ZAP kits from the 1990s. USPTO 656,323 from 1897 shows an electric bicycle where the motor drives the pedal cranks, what we call a 'mid-drive' today. For active members of the current e-bike community, it's a bit surprising to find out that what feels like such a recent idea could have a history so old.

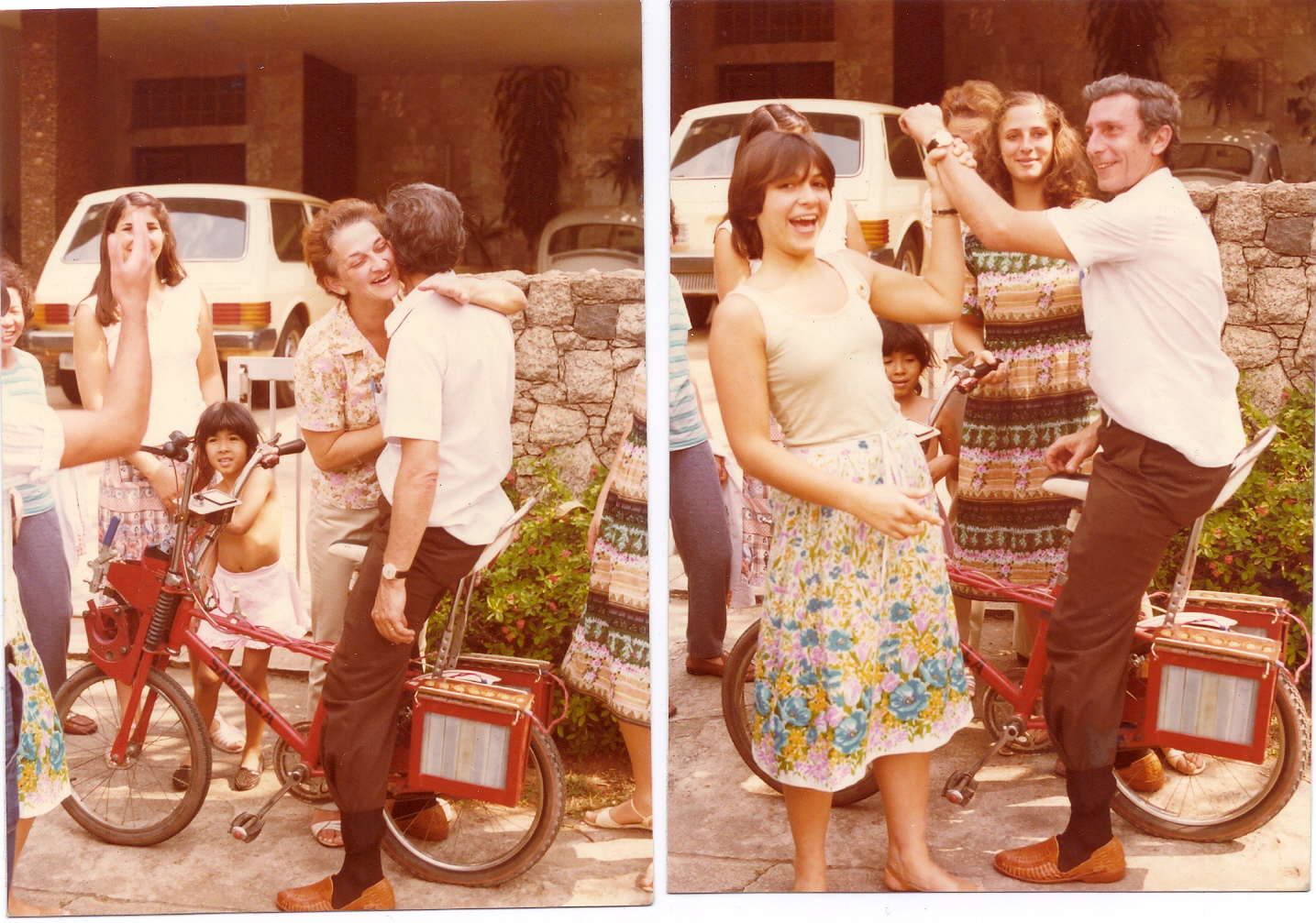

At the end of the 1800s, the heyday of bicycle inventions in the West gave way to a century-long love affair with the automobile and all the effects of that infatuation. In an era when progress meant freeways, when petroleum supplies were unlimited, and bicycles were mostly seen as weekend recreation, it would have been hard to pitch an electric bike as some kind of ground breaking idea. That is the problem that Felicio Sadalla, an industrial engineer and garage inventor from Sao Paulo faced three decades ago. In 1975 he cobbled together a DC motor from a truck radiator, a pile of nickel cadmium batteries salvaged from an airplane scrap yard and an old red two-wheeler to build what may have been Brazil's first e-bike.

At the end of the 1800s, the heyday of bicycle inventions in the West gave way to a century-long love affair with the automobile and all the effects of that infatuation. In an era when progress meant freeways, when petroleum supplies were unlimited, and bicycles were mostly seen as weekend recreation, it would have been hard to pitch an electric bike as some kind of ground breaking idea. That is the problem that Felicio Sadalla, an industrial engineer and garage inventor from Sao Paulo faced three decades ago. In 1975 he cobbled together a DC motor from a truck radiator, a pile of nickel cadmium batteries salvaged from an airplane scrap yard and an old red two-wheeler to build what may have been Brazil's first e-bike.

Felicio felt that bicycles were a much more sensible a means of transportation than the prevailing automobile and that the electric assist could maintain that efficiency with a more widespread appeal. But the timing wasn't right in 1975 for his idea to have any traction. Two years later the parts for his first e-bike were back in the scrapyard. Though Felicio went on to work with electric and then early hybrid cars, the appeal of a simple electric bicycle lingered in the back of his head as concept whose time may one day come.

It was in Japan that electric bicycles first reached any kind of mainstream acceptance. In the mid 1990s some 10-20 percent of the bicycle market was electric assist. But the numbers plateaued, as Japanese e-bikes were said to be designed for and used almost entirely by "old people and housewives,” and had limited appeal to commuters as a whole. A few years later China showed the world just what significant reach electric bicycles can have. The numbers there exploded exponentially, from several hundred thousand at the start of this century to 100-120 million today.

E-bikes in China outsell cars two to one. Their sudden popularity has confounded and stumped planners and traffic engineers trying to pave the way for China to follow in America's tracks and become the next automobile powerhouse. For the Chinese, the e-bike ("Battery Bike" would be the more literal translation) is really an electric scooter. It's a step above the bicycle when you can't afford a car, and in a large nation rapidly rising from a peasant country to a superpower, this describes a lot of people.

Back in America, the motivation for people to embrace e-bikes is quite different; many of the characters currently shaping the electric bicycle scene got started in the early 1990s, well before the Chinese phenomenon. One early adopter was Morgan Giddings, who was pursuing a master’s degree in computer science at the University of Wisconsin in 1993, when she learned of a Californian company called Zero Air Pollution vehicles, better known as ZAP.

Giddings had been a bicycle commuter for the most part, but admits that with a long 10-mile commute she "wasn't necessarily motivated to bike each day." ZAP sold a conversion kit that used a friction roller to rub against and spin the back tire, and although this system had plenty of limitations (roller slippage in the rain, only two speed throttle and lots of drag from the motor), it certainly convinced Morgan of the immense practicality of this idea. "It got me on the bike way more often; that was the key thing."

Giddings had been a bicycle commuter for the most part, but admits that with a long 10-mile commute she "wasn't necessarily motivated to bike each day." ZAP sold a conversion kit that used a friction roller to rub against and spin the back tire, and although this system had plenty of limitations (roller slippage in the rain, only two speed throttle and lots of drag from the motor), it certainly convinced Morgan of the immense practicality of this idea. "It got me on the bike way more often; that was the key thing."

Giddings took her kit through years of use, including maintenance and upgrades. Many people thought her e-bike was pretty neat, but reception from bicycle stores was cool at best. It was this negative attitude from the cycling establishment that largely convinced her to toy with a different career path from academics and bio-informatics.

In 2007 Giddings and her partner Elise opened Cycle9, an electric and cargo bike specialty shop in North Carolina. They wanted to create a space where people could try out and experience e-bikes without the need to be tech savvy and source all the parts on the Internet. They firmly believe the benefits of the electric assist will help overcome challenges to bicycle adoption in the US.

Almost anyone who has spent time on the online e-bike forums, especially in the early 2000s, will have heard or come across Joshua Goldberg, one of the most prolific posters and an enigmatic character who has been scheming and dealing in e-bike parts from his Toronto apartment for two decades now.

Goldberg is a recumbent bicycle devotee and self-proclaimed mechanical klutz, but that didn't stop him. In the late 1980s he rigged up a two horsepower Bosch electric motor to spin the front wheel of his Peugeot to help him bike with his daughter in a trailer.

Goldberg is a recumbent bicycle devotee and self-proclaimed mechanical klutz, but that didn't stop him. In the late 1980s he rigged up a two horsepower Bosch electric motor to spin the front wheel of his Peugeot to help him bike with his daughter in a trailer.

His motivation was, he said, part laziness and, in a larger part, dislike of cars in general, having lost several close family members to motor vehicle accidents. The recumbent bicycle with an electric assist attached just made sense. So when commercial kits such as the ZAP and Currie came out in the 1990s, Goldberg became a key Canadian dealer, serving mostly recumbent riders across the continent.

His motivation was, he said, part laziness and, in a larger part, dislike of cars in general, having lost several close family members to motor vehicle accidents. The recumbent bicycle with an electric assist attached just made sense. So when commercial kits such as the ZAP and Currie came out in the 1990s, Goldberg became a key Canadian dealer, serving mostly recumbent riders across the continent.

It's not too surprising that recumbent bicycle riders made up a disproportionate number of early experimenters in electric assist technology. It’s a community already used to thinking outside the box and it seems intuitive that they would pursue what are clearly superior technologies, regardless of what was happening in the mainstream culture. But even within this niche community, the idea of an electric motor helping a bike created divisions: some embraced it while others derided the whole concept of motorized assistance as akin to cheating or riding a motorbike.

The constant squabble on the recumbent forums led Goldberg to found a new site, the Yahoo "Power-Assist" group, where all topics related to electric drives on bikes and trikes were welcome. This flourished, and for many years was the central hub of the do-it-yourself electric bike movement. With few sources for pre-built e-bikes in North America, most people who caught wind of the idea found out about the availability of kits through the Internet and got drawn into this community.

For some, getting one's hands dirty by refitting and modifying their bicycle to fit a motor and battery was a required part of the process since there was no easy off-the-shelf fix. For others, the whole process of building a homemade e-bike was an obsession in and of itself.

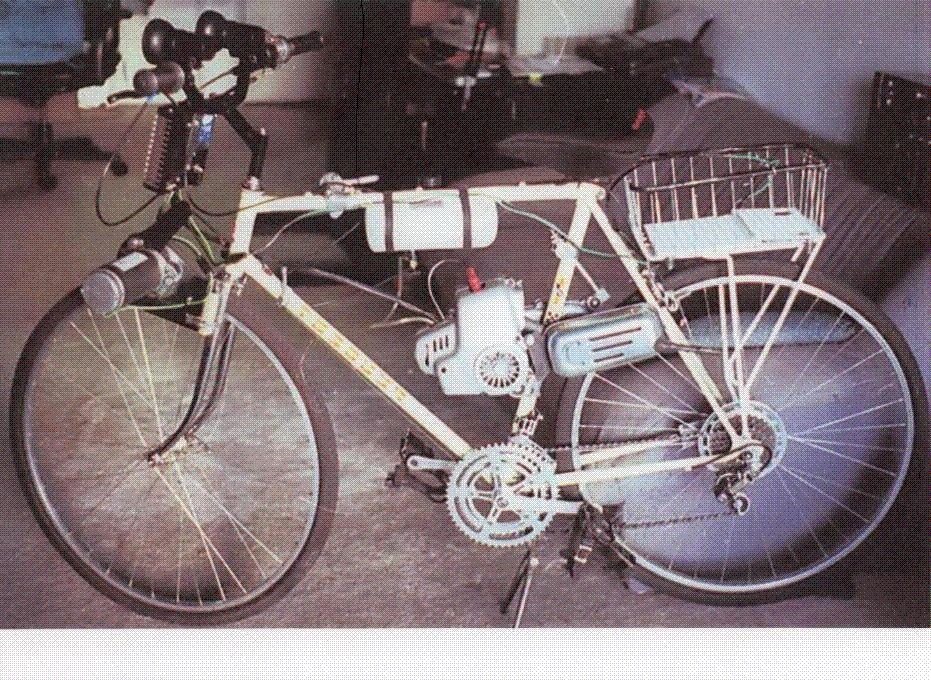

For Barrie Wilkinson, a retired mechanical engineering professor living in Westbank, BC, the electric bicycle has become "a perfect retirement hobby." He first acquired a turn-key imported e-bike in 2004, thinking that this might just be the ticket for the 72-year-old former smoker with arthritis to stay active and regain the enjoyment of cycling.

Wilkinson’s turn-key e-bike had many shortcomings, but it worked well enough to convince him that the electric bike had potential, and that given some time in his garage workshop he could probably make something significantly better. Six years later, Wilkinson has built over half a dozen different conversions, experimenting with hub motors, crank drives and evolving from lead acid to Nickel Metal Hydride to lithium battery packs as these newer and lighter technologies became available.

The presence of an active, passionate and helpful online community has been key for people like Wilkinson to take on this kind of project. “There's no way" he would have undertaken these e-bike projects without the support and guidance of the enthusiasts on the web, he said. While the original Power-Assist Yahoo group lives on, the community today is mostly centered on a web forum at endless-sphere.com.

With over 13,000 topic threads and some 221,000 posts, endless-sphere.com has become an exciting hub of activity for the e-bike movement. From instructions on how to build powerful e-bike packs from hacked apart powertool batteries, to challenges for making the lightest, the most powerful, the fastest or even the cheapest e-bike, it is a place that feels like a new frontier in the Wild West. Characters such as Stéphane Melançon (aka, DoctorBass) tows a school bus with his souped-up e-bike. Others are modifying super-efficient radio-controlled airplane motors to run their e-bikes with just a few pounds of additional weight.

With over 13,000 topic threads and some 221,000 posts, endless-sphere.com has become an exciting hub of activity for the e-bike movement. From instructions on how to build powerful e-bike packs from hacked apart powertool batteries, to challenges for making the lightest, the most powerful, the fastest or even the cheapest e-bike, it is a place that feels like a new frontier in the Wild West. Characters such as Stéphane Melançon (aka, DoctorBass) tows a school bus with his souped-up e-bike. Others are modifying super-efficient radio-controlled airplane motors to run their e-bikes with just a few pounds of additional weight.

Boundaries of technology and innovation are being pushed not by well-funded research labs or big corporations, but by hundreds of individuals who see endless possibilities for pedal-assist electric bikes to transform their lives and maybe the world around them.

It's unlikely that the early electric bike inventors of the late 1800s saw their creation as some kind of clean, minimalistic and efficient alternative to a heavy automobile. Traffic congestion, greenhouse gasses, asthma, sprawling suburbs and epidemic obesity weren't in anyone's rear-view mirror, and so the motor on an early bicycle was just a blip in the march of technological progress and industrialization. But for people like Felicio Sadalla who understood the potential from different angle, there must be some delight in seeing the world finally catching up to this idea. In 2009, Brazil released its first production run of locally-made e-bikes, and Sadalla was honoured with an award and a gift of 10 modern e-bikes from an insurance company for having directed them to this idea.

E-bikes have achieved remarkable success in Europe over the past two years, with over a million units on the road, and out here in North America, a community is hard at work trying to show us what the future may have in store.

© 2010 Justin Lemire-Elmore

Canadian

Canadian